1977 Rolling Stone George Lucas InterviewMay 7, '07 5:09 AM

por Workerantpara todos

The Force Behind Star Wars

George Lucas talks about why robots need love and where Wookies come from

PAUL SCANLON

One sunny spring afternoon last year, an old friend and fellow movie buff drove me to an inconspicuous two-story warehouse in Van Nuys, California. The building was headquarters for Industrial Light and Magic, an organization of young technicians charged with the responsibility of creating special visual effects for Star Wars, writer/director George Lucas' $9.5 million space fantasy.

Lucas and the principal unit had just started shooting in Tunisia, but the activity around IL&M that day was so intense you'd have thought the film was opening in a month or two. Modelmakers were hard at work putting the finishing touches on miniature spacecraft (chiefly by cannibalizing store-brought model kits); a team of animators was hard at work on prototype effects; the explosives people were worrying about upcoming tests and everyone was fussing over the camera that John Dykstra and his technicians had constructed -- from scratch -- to shoot the space sequences.

Dykstra, the film's special photographic effects supervisor, who had worked previously with Douglas Trumbull's (2001: A Space Odyssey), led a bunch of us upstairs to a makeshift screening room littered with chairs and a couple of old overstuffed sofas. One of the young animators had just completed a series of laser blasts for Dykstra's approval. The room went dark and we watched the "lasers" light up the screen. The better ones were greeted with applause; the most spectacular ones got cries of "Wowie!," "Whoopee!" and "Far Out!"

Later, I was peering at some storyboards -- sequential pen-and-ink illustrations -- of a planned space battle scene. Several shots featured a hairy creature with enormous teeth apparently at the controls of a spacecraft. "What's that?" I ask a passing technician. "A Wookie, of course," she replied, and continued walking without further explanation.

Even back then it was pretty easy to see that this young and gifted crew was fired up by George Lucas' peculiar vision and exceptional imagination. He says that all of his films are characterized by a "sort of effervescent giddiness." Whatever you want to call it, it's a quality that seems to affect the people who work for him and audiences alike. His first feature film,THX 1138, was technically brilliant but no crowd-pleaser. Still, it has attained cultish status and has consistently done well through campus rentals over the past few years. Then came American Graffiti, George's paean to the Class of '62, cruising and rock & roll. Made for $750,000 with a small crew and a twenty-eight-day shooting schedule, it has become the eleventh largest grosser. And in case you've been asleep for the past couple of months, or on Mars, George Lucas' third feature, Star Wars, will certainly hit the Top Ten and may well become the biggest grosser ever. Within eight weeks it had taken in $54 million at the box office. George's novelization of the script, released without fanfare by Ballantine Books last winter, was last seen reaching Number Four on the mass-paperback charts, with two million copies now in print. And the posters, T-shirts, models, masks of the main characters and more books are on their way; the soundtrack album is already gold. Not bad for a film that almost never got off the ground in the first place, and was an unknown quantity almost right up to the release date.

When I visited the set in London later that spring, there was a notable lack of effervescent giddiness. It was certainly impressive enough -- all eight of the EMI Elstree Studios' sound stages were in use for Star Wars -- and everything seemed to be on schedule, but George Lucas was worried. Some of the actors were questioning their dialogue. The robots didn't look right. A whole sequence with Peter Cushing had to be reshot because it didn't look right. There were script revisions. The Alec Guinness character was going to be killed off two-thirds into the film, and the studio didn't know it yet. The English crews worked a strict eight-hour day, and had two obligatory tea breaks....

At his home in San Anselmo later that summer, George and producer Gary Kurtz were looking more worried. The studio was demanding a rough cut, and the special effects were barely one-third complete. The robots were looking even worse. The score wasn't ready. There were lightning problems, sound problems...

Somehow -- basically through around-the-clock efforts -- it all came together. A week before opening there was still no answer print. George and the sound people were looping sound effects into the 70-millimeter version right up until the last minute. The only question remaining was, would it fly? It did.

It's not a difficult movie to synopsize. In fact, Star Wars is straight out of Buck Rogers and Flash Gorgon by way of Tolkien, Prince Valiant,The Wizard of Oz, Boy's Life and about every great western movie ever made. Our hero, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) is a farmboy from an arid desert planet called Tatooine who suddenly finds himself-through a series of unlikely events-smack in the middle of a galactic war. His allies include Hans Solo (Harrison Ford), a daredevil space-pilot-for-hire; Ben Obi-Won Kenobi (Alec Guinness), a mystical old gent who is the last of a group called the Jedi knights, and who knew Luke's father when; Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher), who is one of the chief rebels opposing the Empire; Chewbacca, the Wookie, an eight-foot-tall, intelligent and ferocious anthropoid; and two wisecracking robots named Artoo Deetoo and See Threepio (the former speaks android, the latter English) who practically steal the film.

The chief bad guys are Darth Vader (David Prowse) and Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing), aided by a horde of flunkies and storm troopers. They operate out of the Death Star, an enormous satellite designed specifically to go around the galaxy zapping recalcitrant planets unwilling to side with the Empire. It is clear, early in the film, that confrontations are inevitable. It's also clear who's going to win.

What sets Star Wars apart from its predecessors are the special effects (some 365 separate shots) and the extraordinary richness of Lucas' imagination. There's the Cantina sequence, for instance, where the heroes stumble into a bar whose patrons are the scum of a dozen galaxies. And there are ancillary creatures like the Jawas, tiny, chattering beings who hustle used robots for a living. As for the opticals and miniatures, Lucas and Dykstra have come up with a new standard against which all future space-fiction films must be judged. Before Star Wars was released, Dykstra told an interviewer that the final battle sequence would be every bit as exciting as The French Connection car chase. He was right.

So here sits George Lucas, 33, in a hotel suite overlooking New York's Central Park. He's in town to see the premier of his friend Martin Scorsese's film, New York, New York, which was edited by his wife, Marcia (who also cut much of Star Wars). Somewhere out there, folks are queuing up for the next showing of his movie, and George Lucas, fresh from Hawaii, is smiling.

So how does it feel; did you really expect that Star Wars was going to take off like this?

No way. I expected American Graffiti to be a semisuccessful film and make maybe $10 million -- which would be classified in Hollywood as a success -- and then I went through the roof when it became this big, huge blockbuster. And they said, well, gee, how are you going to top that? And I said, yeah, it was a one-shot and I was really lucky. I never really expected that to happen again. After Graffiti, in fact, I was really just dead broke. I was so far in debt to everyone that I made even less money on Graffiti than I had on THX 1138. Between those two movies it was like four and a half to five live years of my life, and after taxes and everything I was living on $9000 a year. It was really fortunate that my wife was working as an editor's assistant. That was the only thing that got us through. I put some of my own money in Graffiti, we were trying to finance it and operate at the same time, and I had been borrowing money from Francis Ford Coppola, my lawyers, my parents and everybody I knew. I really had to get a movie off the ground. And I had worked on Apocalypse Now for four years. I was supposed to do it right after THX. Francis finally bought tile property back. We did everything we could to get it off the ground, but nobody would go for it.

The Apocalypse Now that you wanted to do...

... was completely different than the one Francis is doing now. . . .It was really more of man against machine than anything else. Technology against humanity, and then how humanity won. It was to have been quite a positive film. So what happened was I finally got a deal for very little money to develop Star Wars.

How many studios turned it down?

Two.

And then Fox took it?

Fox took it, and it was close because there wasn't any other place I wanted to take it. I don't know what I would have done, maybe take a job. But the last desperate thing is to "take a job." I really wanted to hold on to my own integrity. So I was going to try to write a very interesting project. Right after Graffiti I was getting this fan mail from kids that said the film changed their life, and something inside me said, do a children's film. And everybody said, "Do a children's film? What are you talking about? You're crazy."

You know, I had done Graffiti as a challenge. All I had ever done to that point was crazy, avant-garde, abstract movies. Francis really challenged me on that. "Do something warm," he said, "everyone thinks you're a cold fish; all you do is science fiction." So I said, "Okay, I'll do something warm." I did Graffiti and then I wanted to go back and do this other stuff, I thought I had more of a chance of getting Star Wars off the ground. I had gone around to all the studios with Apocalypse Now for the tenth time and then they said no, no, no. So I took this other project, this children's film. I thought: we all know what a terrible mess we have made of the world, we all know how wrong we were in Vietnam. We also know, as every movie made in the last ten years points out, how terrible we are, how we have ruined the world and what schmucks we are and how rotten everything is. And I said, what we really need is something more positive. Because Graffiti pointed out, as I said with these letters, that kids forgot what being a teenager was, which is being dumb and chasing girls, doing thing -- you know, at least I did when I was a kid.

Before I became a film major, I was very heavily into social science, I had done a lot of sociology, anthropology, and I was playing in what I call social psychology, which is sort of an offshoot of anthropology/sociology-looking at a culture as a living organism, why it does what it does. Anyway, I became very aware of the fact that the kids were really lost, the sort of heritage we built up since the war had been wiped out in the Sixties and it wasn't groovy to act that way anymore, now you just sort of sat there and got stoned. I wanted to preserve what a certain generation of Americans thought being a teenager was really about -- in a strong sense from about 1945 to 1962, that generation, several generations. There was a certain car culture, a certain mating ritual going on, and it was something that I'd lived through and really loved.

So by seeing the effect Graffiti had on kids, I realized that kids today of that age rediscovered what it was to be a teenager. They also started going out cruising the main street of town again, and I went back and did various studies of towns, my own town, Modesto, we checked them out. There was no cruising and then, all of a sudden, it all started up again. So when I got done with Graffiti, I said, "Look, you know something else has happened, and I began to stretch it down to younger people, 10 to 12-year-olds, who have lost something even more significant than the teenager. I saw that kids today don't have any fantasy life the way we had -- they don't have westerns, they don't have pirate movies, they don't have that stupid serial fantasy life that we used to believe in. It wasn't that we really believed in it....

But we loved it.

Look, what would happen if there had never been John Wayne movies and Errol Flynn movies and all that stuff that we got to see all the time. I mean, you could go into a theater, not just watch it on television on Saturday morning, actually go into a theater, sit down and watch an incredible adventure. Not a stupid adventure, not a dumb adventure for children and stuff but a real Errol Flynn, John Wayne -- gosh -- kind of an adventure.

Or The Crimson Pirate with Burt Lancaster or The Magnificent Seven.

Yeah, but there aren't any. There's nothing but cop movies, and a few films like Planet of the Apes, Ray Harryhausen films, but there isn't anything that you can really dig your teeth into. I realized a more destructive element in tile culture would be a whole generation of kids growing up without that thing, because I had also done a study on, I don't know what you call it, I call it the fairy tale or the myth. It is a children's story in history and you go back to the Odyssey or the stories that are told for the kid in all of us. I can see the little kids sitting there and just being enthralled with Ulysses. Plus the myths which existed in high adventure, and an exotic far-off land which was always that place over the hill, Camelot, Robin Hood, Treasure Island. That sort of stuff that is always big adventure out there somewhere. It came all the way down through the western.

The Western?

Yeah, one of the significant things that occurred to me is I saw the western die. We hardly knew what happened, one day we turned around and there weren't any westerns anymore. John Ford grew up with the West, the very toe end of the West, but he was out there where there were cowboys and shootings in the streets, and that was his American Graffiti, I realized; that's why he was so good at it. A lot of those guys were good at it. They grew up in the Tens and Twenties when the West was for all practical purposes really dying off. But, there was still some rough-and-tumble craziness going on. And the people now, the young directors like me, can't do it because there isn't anything like that anymore.

So you do a Star Wars?

I was a real fan of Flash Gordon and that kind of stuff, a very strong advocate of the exploration of outer space and I said, this is something, this is a natural. One, it will give kids a fantasy life and two, maybe it will make someone a young Einstein and people will say, "Why?" What we really need to do is to colonize the next galaxy, get away from the hard facts of 2001 and get on the romantic side of it. Nobody is going to colonize Mars because of the technology, they are going to go because they think maybe they will be able . . . well, it is romantic, it is the romantic aspect of it that needs to be looked at for a second, which nobody had ever looked at before. I mean, everybody had looked at the hardware end of it.

You firmly establish that at the beginning of Star Wars with the words: "A long, long time ago in a galaxy far, far away . . ."

Well, I had a real problem because I was afraid that science-fiction buffs and everybody would say things like, "You know there's no sound in outer space." I just wanted to forget science. That would take care of itself. Stanley Kubrick made the ultimate science-fiction movie and it is going to be very hard for somebody to come along and make a better movie, as far as I'm concerned. I didn't want to make a 2001, 1 wanted to make a space fantasy that was more in the genre of Edgar Rice Burroughs; that whole other end of space fantasy that was there before science took it over in the Fifties. Once the atomic bomb came, everybody got into monsters and science and what would happen with this and what would happen with that. I think speculative fiction is very valid but they forgot the fairy tales and the dragons and Tolkien and all the real heroes.

So that was the mainspring of your decision to make Star Wars.

Right, and that is really the reason I did it. I had done sociological research on what makes hit films -- it is part of the sociological bent in me; I can't help it.

And yet you encountered a lot of resistance on this project?

Yes. I started out saying this is a fairly viable project, I thought it would make roughly $16 million. The thing is, okay, if I spend $4.5 million, then on the advertising and the prints and everything another $4.5 million, there is a little bit of profit in there, if it makes $16 million. I said this was a good venture, and I could take it to the studios . . . they do marketing and stuff but they don't interpret it properly. The marketing survey is only as good as the people that are interpreting it, and when I went to one Studio, United Artists, I said, this is what I'm going to do. It's Flash Gordon, it's adventure, It's exciting, sort of James Bond and all this kind of stuff, and they said, no, we don't see it. So I went to Universal and got the same thing.

I think I got $20,000 to write and direct Graffiti and they wanted me to do Star Wars for $25,000. 1 was asking half of what my friends were asking, and the studio thought I was asking for twice as much as I would get, and they said, no, no. It is too much money and we don't really think it is for us, so they threw it out the window. And then I finally talked Fox into doing it, partially because they sort of understood, they had done the Planet of the Apes movies, partially just because Laddie, Alan Ladd Jr., understood. He was a project officer then and I guess he saw Graffiti before he made his decision and he said, this is a great movie and what the hell, I was asking for $10,000 just to start this little project. They said, I think it's got potential, so they went with it but nobody thought it was going to be a big hit. I kept doing more research and writing scripts. There were four scripts trying to find just the right thing because the problem in something like this is you are creating a whole genre that has never been created before.

How do you explain a Wookie to a board of directors?

You can't, and how do you explain a Wookie to an audience, and how do you get the tone of the film right, so it's not a silly child's film, so it's not playing down to people, but it is still an entertaining movie and doesn't have a lot of violence and sex and hip new stuff? So it still has a vision to it, a sort of wholesome, honest vision about the way you want the world to be. I was also working on themes that I worked with in THX and Graffiti, of accepting responsibility for your actions and that kind of stuff. So it took me a long time to get the thing done. About the time we finished the preproduction, we did a budget on it. The first budget actually came out to $16 million, so I threw out a lot of designing new equipment and said, okay, we'll cut corners and do a lot of fast filmmaking, which is where I really come from. Graffiti and THX were nothing, both under-a-million-dollar pictures. So we started applying some Of our budget techniques and we got it down by $8.5 million, which was really about as cheap as that script could possibly ever be made by any human being.

When I fist met you in London, you were complaining that you could make a $2 million movie for $1 million but you couldn't make a $14 million movie for $8 million.

It was terribly difficult but we made it. We set the budget for $8 million, they said, no, make it seven. When we finally got the budget down to $7 million we knew it couldn't be done, and we told Fox it couldn't be done. They said make it $7 million anyway. I was practically working for free and my only hope was that if the film paid off, and if it cost $8 million, that would mean it would break even at $20 million.

What was your actual salary for directing?

I think in the end my actual salary was $100,000, which again was still like half of what everybody else was making.

Do you have percentage points in the film?

Everybody has points, but the key is to make them pay off. I figured I was never going to see any money on my points, so what the heck. I also had a chance to give away a lot of my points, which I had done with Graffiti. Part of the success is the fault of the actors, composer and crew and they should share in the rewards as well, so I got my points carved down much less than what my contemporaries have. But I never expected Star Wars to... I expected to break even on it, I still can't understand it.

Why?

I struggled through this movie. I had a terrible time; it was very unpleasant. American Graffiti was unpleasant because of the fact that there was no money, no time and I was compromising myself to death. But I could rationalize it because of the fact that, well, it is just a $700,000 picture -- it's Roger Corman -- and what do you expect, you can't expect everything to be right for making a little cheesy, low-budget movie. But this was a big expensive movie and the money was getting wasted and things weren't coming out right. I was running the corporation. I wasn't making movies like I'm used to doing. American Graffiti had like forty people on the payroll, that counts everybody but the cast. I think THX had about the same. You can control a situation like that. On Star Wars we had over 950 people working for us and I would tell a department head and he would tell another assistant department head, he'd tell some guy, and by the time it got down the line it was not there. I spent all my time yelling and screaming at people, and I have never had to do that before.

I got rid of some people here and there but it is a very frustrating and an unhappy experience doing that. I realized why directors are such horrible people -- in a way -- because you want things to be right, and people will just not listen to you and there is no time to be nice to people, no time to be delicate.

This was something else you said in London: "I'm tired of being a director, I want to go back to being a filmmaker."

Well, that's true, that is really what I want to do. I've done this thing now. I've directed my large corporation and I made the movie that I wanted to make. It is not as good by a long shot as it should have been. I take half the responsibility myself and the other half is some of the unfortunate decisions I made in hiring people, but I could have written a better script, I could have done a lot of things; I could have directed it better.

Back in California last summer you were again upset. You said the robots didn't look right. Artoo looked like a vacuum cleaner. You could see fifty-seven separate flaws in See Threepio, you didn't like the lighting, everything seemed like it wasn't coming together. Was it coming together?

Well, for one thing, by the time we got back to California I wasn't happy with the lighting on the picture. I'm a cameraman, and I like a slightly more extreme, eccentric style than I got in the movie. It was all right, it was a very difficult movie, there were big sets to light, it was a very big problem. The robots never worked. We faked the whole thing and a lot of it was done editorially.

How?

Every time the remote-control Artoo worked it turned and ran into a wall, and when Kenny Baker, the midget, was in it, the thing was so heavy he could barely move it, and he would sort of take a step and a half and be totally exhausted. I could never get him to walk across the room, so we would cut to him there and cut to a close-up, and cut back so that he would be over here. It is all really movie magic more than it was anything else.

That's why it's amazing because when I saw the film I was surprised. I couldn't see any seams. So I went to see it again and maybe saw a couple of seams, but that was it.

I can see nothing but seams. A film is sort of binary -- it either works or it doesn't work. It has nothing to do with how good a job you do. If you bring it up to an adequate level where the audience goes with the movie then it works, that is all. It is a fusion thing and then everything else, all of the mistakes don't count anymore.

Well, the Star Wars audience has no trouble suspending disbelief.

Right. If a film does not work, then you can do an impeccable job with making the movie. People still see the mistakes, and they get bored and it just doesn't work. And so what can you say? THX was about 70% of what I wanted it to be. I don't think you ever get to the point where it is 100%. Graffiti was about 50% of what I wanted it to be but I realized that the other 50% would have been there, if I just had a little more time and a little more money. Star Wars is about 25% of what I wanted it to be. It's really still a good movie, but it fell short of what I wanted it to be. And everyone said, "Well, Jesus, George, you wanted the moon for Chrissake, or you wanted to land on Pluto and you landed on Mars." I think the sequels will be much, much better. What I want to do is direct the last sequel. I could do the first one and the last one and let everyone else do the ones in between.

It wouldn't bother you to have someone else do the ones in between?

No, it would be interesting. I would want to try and get some good directors, and see what their interpretation of the theme is. I think it will be interesting, it is like taking a theme in film school, say, okay, everybody do their interpretation of this theme. It's an interesting idea to see how people interpret the genre. It is a fun genre to play with. All the prototype stuff is done now. Nobody has to worry about what a Wookie is and what it does and how it reacts. Wookies are there, the people are there, the environment is there, the empire is there . . . everything is there. And now people will start building on it. I've put up the concrete slab of the walls and now everybody can have fun drawing the pictures and putting on the little gargoyles and doing all the really fun stuff. And it's a competition. I'm hoping if I get friends of mine they will want to do a much better film, like, "I'll show George that I can do a film twice that good," and I think they can, but then I want to do the last one, so I can do one twice as good as everybody else. [Laughs]

Talking to you as a screenwriter for a moment, rather than a director, you've said Star Wars comes out of bits and pieces of your childhood: Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon, Alex Raymond . . .

True, true.

Now nobody who sees the film questions what a Wookie is, nobody questions what a Jawa is, they accept it right away because the film has a foundation of imagination, an elaborate underpinning of detail that makes these things plausible. So let's take it one step further. Say, for instance, that you were an anthropologist and just came back from the Wookie planet. What would you report?

That's in the earlier scripts. I had actually written four different plots and different stories with different characters, and they involved different environments. In one of the scripts there is a Wookie planet. It's a jungle planet and there was a whole sequence where the Empire had a little outpost on the Wookie planet and Luke [Skywalker] gets involved with the Wookies and he fights the head Wookie. He wins the fight but he doesn't kill the Wookie and the Wookie says, okay, you are going to be the son of the chief and all that kind of stuff. He rallies the Wookies and the Wookies all attack this imperial base. The imperial base has tanks and all kinds of stuff and the Wookies beat them off, and then Luke and Ben [Kenobi] and Han (Solo] and a bunch of people train the Wookies to fly the fighters, and it is the Wookles that go after the Death Star, not the rebels that were on the planet. It was a much different thing, there was a very involved thing with the Wookies. The Wookies are . . . slightly primitive, they live in the jungle, and there is a great sequence which may end up in one of the movies where there is a giant fire and they are all dancing around the fire, all the drums are going and all that kind Of stuff. The Wookies are more like the Indians, more like noble savages.

The Jawas are more like aborigines?

Well, the Jawas are more like scavengers, junk dealers. We had a Jawa village scene in the film but we didn't shoot it because the location was too far away, we just cut that out to keep on budget. We found these great things in Tunisia, little grain houses that were four stories high but with little tiny doors, little tiny windows, it was a hobbit village. So we had a whole sequence with these little hobbit-world slum dwellers but we had to cut it out.

Did you create Jawas and Wookies out of your readings in anthropology?

They didn't really have any basis. The Jawas really came from THX. They were the shell dwellers, the little people that lived underground in the shells. And in a way, part of Star Wars came out of me wanting to do a sequel to THX. Wookies came out of THX too. One of the actors who was doing some voice-over for radio talk, Terry McGovern, came up with the word Wookie.

Didn't I hear his voice in Star Wars?

They're the San Francisco/San Anselmo/George Lucas players, a bunch of disk jockeys, Scott Beach, Terry McGovern. Terry was the teacher in American Graffiti -- they've been in all my movies -- we were riding along in the car one day and he said: "I think I ran over a Wookie back there," and this really cracked me up and I said, "What is a Wookie?" and he said, "I don't know, I just made it up." And I said, "That is great, I love that word." I just wrote it down and said I'm going to use that.

There are lots of great pseudolanguages in the film -- the Wookie, the Jawas, Artoo and Greedo, the hit creature in the Cantina sequence, to name a few. Were these elaborately constructed?

Yes. Right when the film started, We hired two people -- one was an artist, Ralph McQuarrie, and the other was the soundman, Ben Burtt. I just went to one of my old instructors at USC and I asked, who is the best guy you've got, in terms of working on sound? And so Ben spent two years developing sound effects --- he did all the ray guns, spaceships exploding, and toward the end he worked for like three or four months to come in with Artoo. I said I wanted to have beeps and boops and that. Well, it is easy to say that, it's another to take those beeps, boops and sounds and actually make a personality. He spent a long time coming up with sounds. And I would listen to it and I would say, no, no, we need something with a little more sensitivity, he needs to be sadder here, he needs to be happier there. We need to know he's angry here. And he would go back and he would work on the Arp and the Moog, he would talk into the mike and he would run it fast and he would run it slow and he would combine all these things, and he finally came up with it. It didn't sound all the same, like a touch-tone telephone. To some people I guess he still sounds like a touch-tone telephone.

Artoo has a very distinct personality.

Yeah. Ben had to write out the dialogue I never wrote. I just wrote, Threepio says, "Did you hear that," and the little robot goes "beep-a-da-boop," and Ben had to sit there and say, "Hmmm, well, of course I heard that, you idiot." So then he had to take that and he had to translate it. He did the same thing with the Wookie, a combination of a walrus and bear and about five or six other animal sound effects that are all put together in a very sophisticated manner electronically to create one voice.

What about the Jawa language.

Ben started using a lot of African dialects and then he took certain ones, learned the dialogue himself and then sped up the tape. He would get a couple of people in the office and they would go out and yell and talk and do this dialogue and they would speed it up. He did the same with Greedo, who he worked on for months.

Greedo was one of the most imaginative.

We had various ways for him to talk. Some were purely electronic -- we had one word, which was just a person going oink-oink, and if you did it fast enough with the right rhythm and everything it sounds like a very bizarre language. We used harmonizers, we used a lot of electronic equipment; and that didn't work, so finally Ben got together with a graduate student at Berkeley who is a real expert in languages, and he and Ben taped. They went through languages and languages and then they finally made up a language. Ben took it and edited it down, and we had the dialogue written out. In the script it was an actor who actually said the dialogue to begin with. Then we processed that electronically to give it a sort of phasing sound and, well, it was a lot of work.

Who thought up putting subtitles in that sequence?

That was my idea. Somebody thought we should do subtitles on Han's part too, but it would be too confusing, it is hard enough to understand now. The pace of the film is so fast that you have hardly time to read the subtitles because the cuts and everything are so short.

I was fascinated by the relationship between robots and humans. Droids seem to be second-class citizens, as Threepio is quick to point out from time to time. But on the other hand, there is a very warm bond between droids and humans.

Well, the droids were there to serve. Obviously droids are servants of man. They do as they are commanded and all that kind of stuff but at the same time I love droids, they're my favorite people. I didn't want them to be cold robots. Even the robots in THX are very friendly. They're not malevolent. In Star Wars I really wanted to get into the robots and their problems in life; a little equal time for robots, who have taken a lot of shit over the years and have never really had a chance to prove themselves.

Threepio has obvious affection for Artoo.

Right. They were designed as a sort of Laurel and Hardy team. They were the cosmic aspects of the film, the real cosmic aspects, the ones who were supposed to tell the jokes. I didn't want the whole thing to be comedy but I wanted to have a lot of fun. I didn't want the human characters to crack jokes all the time so I let the robots do it, because I wanted to see if I could make robots like humans.

It is true that you considered not using Anthony Daniels' real voice for Threepio.

Yes. It was primarily because of the fact that it was a British voice, and I really wanted to keep the whole thing American.

Some wag on the set in London said that the movie was going to come out sounding like the British versus the Americans.

I tried very carefully to balance the British and American voices so that some of the good guys had the British voices and some of the Bad guys had British voices. I also wanted to keep the accents very neutral. Alec Guinness and Peter Cushing have sort of mid-Atlantic neutral accents, I mean they are not really strongly British. Tony [Daniels] had the most British accent so I said, no, I want to make him American because he is one of the lead characters. I wanted Threepio's voice to be slightly more used-car dealerish, a little more oily. I had an idea of more of a con man, which is the way it was written, and not really a sort of fussy British robot butler. So I tried and tried but because Tony was Threepio inside, he really got into the role. We went through thirty people that I actually tested, but none of the voices were as good as Tony's, so we kept him.

Whose voice belongs to Darth Vader?

That's James Earl Jones. He was the best actor that I could possibly find. He has a deep, commanding voice.

Was the other Darth Vader angry that his voice was knocked out?

No, he sort of knew when we hired him. He is an actor, David Prowse, and he has a very strong brogue. He played the weight lifter in A Clockwork Orange. He owns a chain of weight-lifting gyms, is very rich and does movies for fun.

Why does Darth Vader breathe so heavily?

I had wanted to do that and tie it in with the dialogue.

It was a nice touch, because it adds to the bogyman quality of the character.

Ben had a lot of work in that too. He did about eighteen different kinds of breathing, through aqualungs and through tubes, trying to find the one that had the right sort of mechanical sound, and then decide whether it would be totally rhythmical and like an iron lung. That's the idea. It was a whole part of the plot that essentially got cut out. It may be in one of the sequels.

What's the story?

It's about Ben and Luke's father and Vader when they are young Jedi knights. But Vader kills Luke's father, then Ben and Vader have a confrontation, just like they have in Star Wars, and Ben almost kills Vader. As a matter of fact, he falls into a volcanic pit and gets fried and is one destroyed being. That's why he has to wear the suit with a mask, because it's a breathing mask. It's like a walking iron lung. His face is all horrible inside. I was going to shoot a close-up of Vader where you could see the inside of his face, but then we said, no, no, it would destroy the mystique of the whole thing.

I was quite happy, to see Vader spinning off into deep space at the end, but not dying. The only thing missing was a title on the screen saying, "To be continued soon at a theater near you."

Right, the idea was doing the film on a practical level and leaving room for sequels. When I did THX I realized that I put in an enormous amount of effort that I will never be able to use again. I know the world of THX. I could make movies about THX forever but it took me so much time and so much energy to develop all that stuff, and then it got touched upon in one movie. Normally in a movie it's maybe a book or a piece of history or a piece of my life. I sat down and wrote Graffiti in three weeks, it was easy. With something like Star Wars, you have to invent everything. You have to think of the cultures and what kind of coffee cups they are going to have, and where is the realm between technology and mankind and where does ESP play a part of this.... And you go and sort of find the levels that you want to deal with. How far out do you want to go? Will the people relate to that?

It will be interesting to see how Star Wars does overseas.

Yeah. Star Wars is designed with the international market in mind. The French are very much into this genre. They understand it more than Americans do, and it is the same with the Japanese. I own a comic gallery, an art gallery in New York that sells comic art and stuff; the guy that runs the art gallery also runs a comic store and we do a lot of business in France. They understand Alex Raymond, they understand that he was a great artist, they understand Hal Foster and they understand comic art as real art and as a sort of interesting, goofy thing. And I am very much into comic art, and its place in society as a real art, because it is something that expresses the culture as strongly as any other art. What Uncle Scrooge McDuck says about America, about me when I was a kid, is phenomenal. It is one of the greatest explorations of capitalism in the American mystique that has ever been written or done anywhere. Uncle Scrooge swimming around in that money bin is a key to our culture. [Laughs] Hal Foster was a huge influence in comic art and, I think, art in general. Some of the Prince Valiants are as beautiful and expressive as anything you are going to find anywhere. It is a form of narrative art but because it is in comic it has never been looked at as art. I look at art, all of art, as graffiti. That's how the Italians describe the hieroglyphics on the Egyptian tombs, they were just pictures of a past culture. That is all art is, a way of expressing emotions that come out of a certain culture at a certain time. That's what cartoons are, and that's what comics are. They are expressing a certain cultural manifestation on a vaguely adolescent level but because of it, it is much more pure because it is dealing with real basic human drives that more sophisticated art sometimes obscures. Do the inevitable comparisons between Star Wars and 2001 bother you?

No, I expected actually a lot more than it got. In fact, I am fairly pleased that they haven't compared it that much to 2001. Actually it is being compared more to westerns than 2001, which is really what it should be. On a technical level it can be compared, but personally I think that 2001 is far superior. You know it had ten times more money and time and obviously it came out better. In special effects one of the key elements is time and money. Most of those special effects in Star Wars were first-time special effects -- we shot them, we composited them and they're in the movie. We had to go back and reshoot some, but in order to get special effects right, you really should shoot them two or three times before You figure out exactly how it should work, which is why it costs so much money. But most of our stuff we had to do as a one-shot deal. We did a lot of work but there is nothing that I would like to do more than go back and redo all the special effects, have a little more time.

Which takes us back to this period of the last few months before release. The editorial that you were mentioning earlier, pulling things together by sleight of hand. What was it like leading up to the actual opening night? I heard that you were looping and cutting up to the last minute.

The whole picture was very difficult because it was made on a very short schedule -- about seventy days on the sets and locations. In England we couldn't shoot past 5:30 so we worked eight-hour days. Whereas I visited Steve [Spielberg] and Marty [Scorsese] after I finished shooting and they were filming 12-14 hours a day. So they were actually getting another day's work every day. They would have, like, a 120-day schedule, but if you counted the hours, they really had 200 days to shoot. While I had seventy real days to shoot, and it was very short for something that was that complex. It was the same in the finishing. The Studio wanted to finish it for the summer, I wanted to finish it for the summer, and so we were up against the wall. When I came back from England, we were supposed to have half of the special effects done and actually they had about three shots finished and they were not up to what I felt were the standards of the film. Industrial Light and Magic had spent most of the early part of that year and a million dollars -- which was about the whole budget in the whole time they had to shoot -- building cameras and developing electronic computer systems and stuff. They didn't really concentrate that much on actually making shots.

Were the cameras that shot the miniatures built from scratch?

Yes, everything was built from scratch. We built optical cameras, moviolas, a whole system based on VistaVision. John Dykstra built it and he really is a very talented guy who worked as a cameraman for Doug Trumbull. He is very, very knowledgeable in building sophisticated camera-motion systems. He developed systems along with several of the people who worked with him in electronic and mechanical designs. It was quite extraordinary; we built a whole operation.

But you and Dykstra were at odds a lot, weren't you?

Well, we weren't so much at odds as much as I was more interested in the shots. I didn't care how we got the shots, I just wanted the composition and the lighting to be good, and I wanted them to get it done on time. On a real production you have no time and you are doing the impossible every day, at a very hectic, accelerated pace. Special-effects people have a tendency to think that if they get one shot a day, they are really quite pleased. They don't work on the same pace that the regular production unit works. I believe that you can do special effects with the same intensity and in the same schedule that you shoot a regular movie, so there was a little bit of conflict there. And at the same time, I wanted the shots to look a certain way and be designed a certain way and we had difficulty with what was actually technically possible with the time laid out to accomplish it. It was purely a working problem and being at odds with John was no greater than being at odds with everybody else. I had just as many problems with the robots and the special-effects people in England as with the special-effects people in California.

Was that one of your key administrative problems then, the wedding of the location footage with special-effects footage?

No, I was just trying to get the special effects up to a quality that I wanted. I was happy with a lot of the special effects toward the end. The operation got very good. In the beginning the cameraman was still learning how to fly the airplanes, because it was a very complex animation thing, where you're moving cameras and rolling, doing little motor things. When you watch it happen you are not working in real time; it is very difficult to plot out the way one of those planes move in non-real time, using tilting cameras and motors. It's easy to take your hand and say, I want the plane to go this way, and it is very difficult to actually translate that onto paper and then film so that you actually get the ship to do that, and it took a long time just to figure out how to fly. There are problems that have never really been coped with before. In 2001 the ships run a straight line, they just go away from you or they cross the screen, they never turn or dive.

What about the final battle sequence, the dogfight?

The dogfight sequence was extremely hard to cut and edit. We had storyboards that we had taken from old movies and we used the black and white footage of old World War II movies intercut with pilots talking and stuff, so you could edit the whole sequence in real time. My wife, Marcia, can normally cut a whole reel -- all ten minutes of the film -- in one week. I think it took her eight weeks to cut that battle. It was extremely complex and we had 40,000 feet of dialogue footage of pilots saying this and that. And she had to cull through all that, and put in all the fighting as well. Nobody really has ever tried to interweave an actual plot story into a dogfight, and we were trying to do that, however successful or unsuccessful we were.

How about the John Williams score? Pretty stirring stuff.

I was very, very pleased with the score. We wanted a very sort of Max Steiner-type, old-fashioned, romantic movie score.

It's very much like a serial -- like, of course, 'Flash Gordon' -- you hear it throughout the film.

There are ninety minutes of music in a 110-minute film. I wanted to use some of Liszt, Dvorak, some of the Flash Gordon stuff and Johnny said no. He wanted to make some strong theme, fairly reminiscent in a few places but at the same time very original. The whole thing was really designed like Peter and the Wolf. We did it so that each character has their own theme and whenever that character is on the screen that theme is played.

A space opera.

Well, they used to do it all the time, writing music for movies was closer to writing for opera or symphony. One interesting thing about the music -- which is sort of like the movie itself -- is that I really expected to get devastated in terms of people saying, "Oh, my God, what a stupid, old-fashioned thing and how corny can you get?" I am amazed that people just said, "Gee, that's fine." I really expected to get trounced very badly about the whole thing. And Johnny did too, a little bit. A lot of the lines in the movie are sort of . . . I wince every time I hear them.

You mean you expected to get trounced on everything? I thought we were just talking about the score.

I expected to get trounced on everything. Especially in the end when it came down to the score, which was romantic and dramatic. Not only a slightly corny dialogue here and a very simplistic, sort of corny plot...

Some of Mark Hamill's lines are pretty corny.

There is some very strong stuff in there. In the end, when you know better, it sort of takes a lot of guts to do it because it's the same thing with the whole movie -- doing a children's film. I didn't want to play it down and make it a camp movie, I wanted to make it a very good movie. And it wasn't camp, it was not making fun of itself. I wanted it to be real.

Even though Harrison Ford's character, Han Solo, is right up to the edge of camp, very John Wayne-ish.

He goes as far as I let anybody go.

"I've been from one end of this galaxy to the other, kid . . ." But he did pull it off.

[Laughs] It fits in his character. Harrison is an extremely intelligent actor and we balanced on a lot of thin threads when we went through this movie. And when you're doing it you never know when you are going to jump off the other side, which is one of the things like with the score. There were a lot of little discussions about if this or that would make it go too far, would it be too much. I decided just to do it all the way down the line, one end to the other, complete. Everything is on that same level, which is sort of old-fashioned and fun but going for the most dramatic and emotional elements that I can get.

The Peter Cushing character, Grand Moff Tarkin, certainly applies to that formula. He got off some great lines. Especially right near the end, "Abandon the station, now at the hour of my greatest triumph?"

The stuff in that is very strong. Peter Cushing, like Alec Guinness, is a very good actor. He got an image that is in a way quite beneath him, but he's also idolized and adored by young people and people who go to see a certain kind of movie. I think he will be remembered fondly for the next 350 years at least. And so you say, is that worth anything? Maybe it's not Shakespeare but certainly equally as important in the world. Good actors really bring you something, and that is especially true with Alec Guinness, who I thought was a good actor like everyone else, but after working with him I was staggered that he was such a creative and disciplined person. In the original script Ben Kenobi doesn't get killed in the fight with Vader. About halfway through production, I took Alec aside and said I was going to kill him off halfway through the picture. It is quite a shock to an actor when you say, "I know you have a big part and you are going to the end and be a hero and everything and all of a sudden I have decided to kill you," but he took it very well and he began to build on it and helped and developed the character accordingly.

Was the studio upset when you told them Kenobi would die?

Everybody was upset. I was struggling with the problem that I had this sort of climactic scene that had no climax about two-thirds of the way through the film. I had another problem in the fact that there was no real threat in the Death Star. The villains were like tenpins; you get into a gunfight with them and they just get knocked over. As I originally wrote it, Ben Kenobi and Vader had a sword fight and Ben hits a door and the door slams closed and they all run away and Vader is left standing there with egg oil his face. This was dumb; they run into the Death Star and they sort of take over everything and they run back. It totally diminished any impact the Death Star had.

It was like the old Bob Steele westerns where they all had about fifty shots in their six-shooters.

Right, but those kind of things dissipate without having a lot of real cruel torture scenes and real unpleasant scenes with the bad guys in order to create them as being bad or make them a threat. I was walking that thin line between making something that I thought was vaguely a nonviolent kind of movie but at the same time I was having all the fun of people getting shot. And I was very careful that most of the people that are shot in the film were the monsters or those storm-troopers in armored suits. Anyway, I was rewriting, I was struggling with that plot problem when my wife suggested that I kill off Ben, which she thought was a pretty outrageous idea, and I said, "Well, that is an interesting idea, and I had been thinking about it." Her first idea was to have Threepio get shot, and I said impossible because I wanted to start and end the film with the robots, I wanted the film to really be about the robots and have the theme be framework for the rest of the movie. But then the more I thought about Ben getting killed the more I liked the idea because, one, it made the threat of Vader greater and that tied in with The Force and the fact that he could use the dark side. Both Alec Guinness and I came up with the thing of having Ben go on afterward as part of The Force. There was a thematic idea that was even stronger about The Force in the earliest scripts. It was really about The Force, a Castaneda Tales of Power thing.

Well, then, theoretically there could be a sequel about The Force, there could be a sequel about the Wookies, about Han, about Luke. . .

Yes, it was one of the original ideas of doing a sequel that if I put enough people in it and it was designed carefully enough I could make a sequel about anything. Or if any of the actors gave me lot of trouble or didn't want to do it, or didn't want to be in the sequel, I could always make a sequel without one.

Do you have agreements with the principal characters?

Yes. All the actors except Alec Guinness. We may use his voice as The Force -- I don't know. One of the sequels we are thinking of is the young days of Ben Kenobi. It would probably be all different actors.

Let's talk about the Cantina sequence. As I remember, there were problems in London.

Stuart Freeborn, the special-effects and makeup man, spent a lot of time and energy on the Wookie and did a fantastic job, and he was rushed to try to create the Cantina creatures while we were shooting in Tunisia. We moved the Cantina sequence up a week in the shooting schedule and I kept adding monsters all the time. So a few weeks before we were going to shoot that sequence Stuart got sick and had to go to the hospital, and so we didn't get all the monsters finished that we wanted to have. The ones we had were the background monsters and they weren't meant to be key monsters. I always knew eventually either Stuart or somebody would come back and shoot more monsters.

So when did you actually finish it?

When we got back to California we cut the film, looked at it and I still didn't think the Cantina scene worked as well as it should have. So I wanted to shoot a second unit. That can get pretty expensive, and the studio said no way you're gonna spend any more money on this picture, because we were already like a million dollars over the budget. And I said it is one of the key scenes in the movie and we have to have more monsters. And so we did a budget and talked to Alan Ladd Jr. It was really his project, and by now he was the president of the company. Ladd said do it, but the only way we would get away with it was if we could do it for $20,000, and so I said, okay, I'll do it for $20,000. So we ended up having to cut out half of what we wanted but it was sufficient. You know, I really wanted to have horrible, crazy, really staggering monsters. I guess we got some but we didn't come off as well as I had hoped.

The band in their black zoot suits is absolutely marvelous. Why were they playing Forties music?

I planned to use Glenn Miller for that sequence originally, but we couldn't use it and Johnny had to come up with something familiar and I think he did a fairly good job. He came up with a really bizarre sound that was very Forties, yet very odd. The whole thing was originally designed as a big-band number, but worked out.

The sequence where Han Solo's ship hits light speed -- hyperspace -- gets a cheer every single time. People just love it.

Technically it was very simple. The actual jump to hyperspace is sort of a pull-back on stairs and then a shot of the ship disappearing real quick. I think more than anything else it is fun because the editing and the design of the sequence before it are very good. It's from the point where the troops start shooting at them to the point where the ship takes off and there are about two very good music cues in there.

It's a chase scene.

You're rooting for them to get away. It's a real flashy escape, you know. There's nothing like popping the old ship into hyperspace to give you a real thrill.

I felt one scene didn't quite work: the one where they almost get crushed by the moving walls in the trash bin. That octopus creature was unsatisfying. I believe it was called a Dia-noga in the script.

The Dia-noga was originally supposed to be a giant, sort or filmy, clear, transparent jellyfish kind of thing that came shooting out of the water, with all these jellylike tentacles with little veins running through them. So first the special-effects people came up with this giant 8-foot-high, 12-foot-wide brown turd that was bigger than the set, and that just didn't work. We finally got it down to where it was just one tentacle. That was all they could really accomplish.

And an eyeball.

Well, the eyeball we did later, we did that in California with the second unit; we did that in the backyard. I never really got a monster. They spent all enormous amount of money building these giant things with hydraulics and all kinds of stuff and they looked terrible. And I said, I only want something sort of ethereal. But they kept wanting to build these giant things and I said, you don't need that, let's just put a bunch of cellophane on a string and pull it up out of the water or something. It got I so ridiculous, I finally just said look, give me one long tentacle. What I really would have liked to have had was a bunch of tentacles. I have always had a problem with that scene. There was one like it in THX which I had cut out. He fell into a trash masher, and there was a giant ratlike creature in there with him. I have never been able to accomplish it, and I don't know why.

The creature is in there to eat the garbage?

Yes, he eats the garbage. The idea was the Dia-noga knows that the doors are going to close and the walls are going to close in and mash the garbage, and he sort of pushes himself against the floor and does whatever he does to survive, and he can't eat the kid right then. It's a slightly esoteric idea. I still want the sequence and someday I will get something on the screen.

The film's success should guarantee some success in the merchandising program you've launched.

One of my motivating factors for doing the film, along with all the other ones, was that I love toys and games. And so I figured, gee, I could start a kind of a store that sold comic art, and sold sevety-eight records, or old rock 'n' roll records that I like, and antique toys and a lot of things that I am really into; stuff that you can't buy in regular stores. I also like to create games and things, so that was part of the movie, to be able to generate toys and things. Also, I figured the merchandising along with the sequels would give me enough income over a period of time so that I could retire from professional filmmaking and go into making my own kind of movies, my own sort of abstract, weird, experimental stuff.

So now you want to sell toys and games, and make esoteric films?

Yes. The film is a success and I think the sequels will be a success. I want to be able to have a store where I can sell all the great things that I want. I'm also a diabetic and can't eat sugar and I want to have a little store that sells good hamburgers and sugarless ice cream because all the people who can't eat sugar deserve it. You need the time just to be able to retire and do those things, and you need to have an income ....

The Star Wars money . . .

. . . will be seed money to try to develop a store and do the other things that I want to do. I've made what I consider the most conventional kind of movie I can possibly make. I've learned my craft in the classic entertainment sense as well as I think I can learn it. What I want to do now is take my craft in the other direction, which is telling stories without plots and creating emotions without understanding what is going on in terms of purely visual and sound relationships. I think there is a whole world of film there that has never been explored. People have gotten so locked into the story film -- the novel and the play have such a strong influence over film that it has sort of become the weak sister. And if the films work, I will try to get them out and get them distributed by whoever would be daring enough to pick them up. Maybe they will be entertaining, it's hard to know at this point. It is in an area that I have absolutely no way of knowing what would happen and that is what excites me. And I have reached the point now that I can say, well, I am retiring. Because I can really retire now.

I have never been like Francis and some of my other friends who are building giant empires and are constantly in debt and have to keep working to keep up their empires. But he is trying to create an independence that we are all trying to create, an independence from having tile studios dictate what kind of films are made.

You keep in touch with Stephen Spielberg, Michael Ritchie, Phil Kaufman, Brian DePalma and Martin Scorsese. . .

There are several groups. There is what we call the USC mafia -- Bill Huyck, Matt Robbins and John Milius -- and then there is the New York contingent: Brian and Marty and Steve were at Long Beach State the same time we were at USC. We became close friends and whatever competition there was was very healthy. Francis and I are really much closer because we have been partners. I know my friends by their movies. It's strange, really. Francis is just like his movies and Marty is just like his movies and Brian is especially like his movies. We collaborate on each other's work. They all came and looked at Star Wars and made their suggestions.

You must be getting some pressure from your peer group not to retire.

Yes, I have. The big thing now is that nobody believes it, especially Francis. He refuses to accept the fact that I am going to do it. When I say "retire" everyone thinks that I am going to go and live in Hawaii for the rest of my life. I'm not, I'm starting sort of a toy-store operation. I'm making my own sort of experimental films. At the same time I am going to be an executive producer on the Star Wars sequels, which is really just a way of making a living but at the same time I'm going to follow through on the stuff I've already started. And who knows? Something may come along and I may direct something again but I think I can be more effective as an executive producer.

When does Star Wars open overseas?

It opens in Europe in October. And then I think it will open next July in Japan. I like Japan. I was going to shoot THX there and I spent some time over there. My wife says I am a reincarnated shogun, or at least a warlord. I'll be fascinated to see what happens over there; Star Wars is slightly designed for Japan.

It's not a Toho production; a Godzilla movie.

No, science fiction has reached this very crummy level in Japan. They love it but it is still very crummy. It's been exploited just like they did in this country. The wrong people have been doing science fiction. Science fiction -- speculative fiction -- is a very important genre that has not been taken very seriously, including the literature.

And there are important ideas there.

Yeah. Why do space suits look the way they do? Why, when we went to the moon, did the astronauts look just like men who went to the moon in Destination Moon?

Which was made in 1950.

Because the art director designed those space suits based on what he thought they would look like in terms of scientific input. But when you get down to it, a bunch of art directors from a bunch of old movies and speculative pulp fiction drew space suits and stuff way back when, and I have a feeling that they had a lot of influence on the way things look today, and the way things are, because the engineers and designers and all those people grew up.

Also, just on a theoretical/philosophical level the ultimate search is still the most fascinating search, what is it all about -- why are we here and how big is it and where does it go, what is the system, what is the answer, what is God and all that. Most civilizations, whole cultures and religions were built on the "science fiction" of their day. It is just that. Now we call it science fiction. Before they called it religion or myths or whatever they wanted to call it.

The epic and heroic tradition.

Yes. It has always been the same thing and it is the most significant kind of fiction as far as I am concerned. It's too bad that it has gotten that sleazy comic-book reputation, which I think we outgrew a long time ago. I think science fiction still has a tendency to react against that image and try to make itself so pious and serious, which is what I tried to knock out in making Star Wars. Buck Rogers is just as valid as Arthur C. Clarke in his own way; I mean, they are both sides of the same thing. Kubrick did the strongest thing in film in terms of the rational side of things, and I've tried to do the most in the irrational side of things because I think we need it. Again we are going to go with Stanley's ships but hopefully we are going to be carrying my laser sword and have the Wookie at our side.

So now you have made your bid.

So I made my bid to try to make everything a little more romantic. Jesus, I'm hoping that if the film accomplishes anything, it takes some ten-year-old kid and turns him on so much to outer space and the possibilities of romance and adventure. Not so much an influence that would create more Wernher von Brauns or Einsteins, but just infusing them into serious exploration of outer space and convincing them that it's important. Not for any rational reason, but a totally irrational and romantic reason.

I would feel very good if someday they colonize Mars when I am ninety-three years old or whatever, and the leader of the first colony says: "I really did it because I was hoping there would be a Wookie up here."

Posted May 25, 1977 12:00 AM

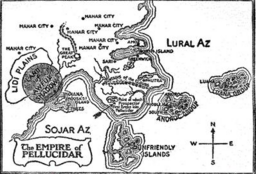

) uma zona sob um eclipse perpétuo chamado Thuria criada pela sombra da lua geoestacionária de Pellucidar.

) uma zona sob um eclipse perpétuo chamado Thuria criada pela sombra da lua geoestacionária de Pellucidar.